Improving Physical and Mental Infrastructure Will Lead to More Competitive Guatemalan Workers

When American Vice President Kamala Harris visited Guatemala in June 2021, her mission was one of fact-finding, initiating a dialogue with the president of Guatemala and exploring the roots of migration. Primary, the central question focused on why many individuals choose to attempt the arduous journey northward that sometimes, results in death.

Missing from the drumbeat of the news cycle isn’t just individuals from the Northern Triangle of Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras that are leaving their home countries, as it also includes those who are coming from points across the Atlantic Ocean, then are migrating either North to the United States or South to select countries in the Southern hemisphere. However, those that live in the larger Central America cities have some established routine that is focused around producing income that benefits the family unit.

In Guatemala, there is a plethora of what would be considered mom and pop stores. I would recognize these as sole proprietorship business concepts and they are very beneficial in that the profits generated remain mostly with the proprietor and/or family.

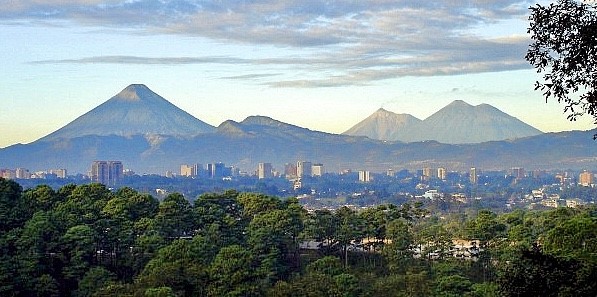

There is no broad brush in which to paint how to move from these mom and pop stores/sole proprietorship to one that results in enhanced profits. Evidence in countries around the world demonstrate the concept of big box stores and the ruination of traditional sole proprietorship storefronts. In the capital city of Guatemala, there is ample evidence of both, the mom and pop stores as well as a growing, larger cadre of big box stores along with efficient workers everywhere dressed professionally and demonstrating a willingness to embrace capitalistic tendencies. There are trade-off’s in both concepts.

These workers commute from points well outside the city starting at five in the morning to be at work by eight a.m., only to reverse the commute in the late afternoon. Only the privileged are blessed to live in the city where they work. Such is true with most major cities around the world.

In commerce and business circles, there is anecdotal awareness that Guatemala has traditionally lagged somewhat with its Latin American counterparts in regards to a numerous competitiveness indicators. However, recently and prior to the pandemic, there was a growing body of data that was showing competitiveness improvement. In 2018, Guatemala was ranked in a dismal 97 out of 140 economies when it came to competitiveness. Guatemala has ranked lower than 13 of its Latin American and Caribbean counterparts, but not lower than those in the Northern Triangle. Future, post-pandemic measurements will be fraught with challenges for all participating countries around the world. But, how does one measure ‘competitiveness’ as something more than a nebulous tangent?

Using a variety of barometers that include internet speed, steel production, inventory modifications, ease of doing business, corporate tax structure, employee productiveness, etc., Guatemala recognizes the dearth of shared commitments from business, industry and governmental entities to all move in the same direction. Incomplete and nontransparent data clouds a realistic view of what competitiveness is and can offer Guatemalans on the world economic platform.

Various entities are laying the foundation to increase the so-called “competitiveness factor” and it is evident in entry level employment such as call-centers, retail stores, hospitality, tourism industry and even drive-through lanes of fast-food restaurants. Guatemala could significantly move up the competitiveness scale using those same barometers by the end of the 2020s. Thus far, countries such as Israel, Korea, Russia and China are providing investments in the country.

Their improved efforts are noted, and it is vastly different from career level employment which consistently are on par with other developed countries around the world. As workplace structure gains an edge, with that comes growing competitiveness. These ideals are essential to promote stability for the younger (16–27 years of age) demographics that seek employment in the public and private sectors, not only in the capital city, but in emerging industrial economic opportunity zones closer to the port facilities of San Jose/Port Quetzal and other regional cities.

Much as it is the case with many K-12, pre-secondary students in developed countries around the world and the United States, the idea to prepare a workforce that has marginal educational experiences also exists in Guatemala. Many students come with minimal literacy skills and/or are lacking in soft-skills, people-to-people dialogue; of course, the Coronavirus/Pandemic only magnified the inability to interact.

A potentially troubling trend that suggests an even more precarious future for this demographic is that of the inappropriately named ‘Neither Nor’ (because they neither study nor work), young people who lack opportunities because public or private schooling is not available to provide them with a basic education.

In Guatemala, a free, public education is not guaranteed and as a result, many children grow up functionally illiterate. Fortunately for the multitude of non-government organizations (NGO’s) there is a very healthy, albeit emerging trend to coalesce around American benefactors to provide funding and education for those individuals that can reach a school site and learn.

One such program, Amigos De La Santa Cruz, based in the Lake Atitlan region southwest of Guatemala City has emerged as a strong regional, reputable leader, changing lives, one generation at time. Their focus is on literacy, education and economic sustainability with the tourism industry that Lake Atitlan is well known for. These rare, bright spots can certainly be duplicated in other areas but growth and results are not instantaneous. Programs such as these are responsive to the needs of the community and genuinely grow organically by listening consistently to what the local population can communicate is needed.

According to ASIES study going back nearly a decade, Nivel educativo e ingresos laborales en Guatemala, 2002–2017 (Level of Education and Labour Income in Guatemala, 2002–2017), out of an estimated total of 4.9 million young people between the ages of 15 and 29 in 2017, 26 per cent neither study nor work, an increase of 4 per cent compared with 2002.

For these students to receive an education, there needs to be the infrastructure in place, whether it be primary or secondary. Physical school sites outside of the capital city are far from abundant; rather it is considered an exclusive privilege for those who can afford the discretionary spending to pay for minimal tuition.

Another NGO, The Hug It Forward organization focuses on building schools with respect to the environment. It is known best for using plastic recycled bottles to support the space in between reinforced walls. After being placed in the cavity of the wall, then, the exterior is solidified with stucco. For such an impressive feat, there is virtually no difference in the finished product and a school site can be prepared much faster than traditional constructional methods. Schools need to be connected to the larger community, along with the basics inclusive of electricity, potable water, toilets, continuous maintenance and cleaning of facilities.

Secondary sources of infrastructure development include basic adequate housing surrounding these school sites, septic/sewer services, potable water supplies, etc. Although even basic housing needs in a country with not enough jobs for everyone continue to be a challenge, various NGO’s continue to help build homes, often with church mission trips. Once the land has been confirmed as belonging to the family, then a cinderblock home can be constructed. With regards to both large scale residential and commercial permitting process, it is periodically fraught with a regulatory, burdensome processes that sometimes make no sense to outside investors.

Some have expressed opinions in securing building/construction permits as extremely challenging, others share that the process is corrosive and fraught with petty and large scale grift. Yet, when beneficial, corruption in of itself does at times, lead to eliminating a step or two to advance a commercial project expeditiously and this isn’t limited to buildings as it can include road projects.

Although the potential for corruption with road projects are evident, grifting can and at times, does yield rapid results with corridor projects being completed faster. As Guatemala continues to expand road capacity, planned highway construction is designed to link the southern, northern and western regions of the country in economic opportunity corridors/zones. Where new roads are constructed, housing would follow organically, along with schooling and ideally, technical skills training centers.

Development in an environment such as countries in the Northern Triangle take nerves of steel to mitigate challenges from several different angles.

The topography of Guatemala is such that in the span of a kilometer or two, the elevation increases and decreases significantly. A huge influx of funding would be necessary to design a travel corridor that is on par with other developed nations that connects port facilities to urban centers, but in this era of climate change, (sustainability and alternatives that lend to stability) Guatemalans are reinventing a future protocol that addresses these concerns; something that other countries can learn from. Where there is strength with infrastructure development, there is also weakness that can be engineered.

As these road projects are implemented, the cost is presumably less emphasis and/or regards to environmental safeguards that protect indigenous populations or the land, but probably both. Compared to North America and Europe, construction projects move at a remarkable clip in Guatemala, in some cases, at half the time it would take to complete a similar project. The Autopista (highway) Palin-Escuintla extension (just over 22 kilometers) is a prime example, completed prior to 2015 and connects to the coastal port city of Puerto Quetzal. Successfully completed and equally distanced between two very active volcanoes, each completed portion of this four-lane highway project brings port, cargo and tourist traffic further inland, closer to the capital city and then beyond, from the Guatemalan lowlands (Pacific side) and more to the Guatemalan Highlands (and eventually to the Caribbean side).

Returning to the capital city, additional road projects continue to be planned and constructed. Recently, an additional toll road that would skirt the southern portion of the city was inaugurated and now connects to the city of Carretera (southeast of Escuintla) with Villa Canales. This newly built toll-road parallels the northern portion of Lake Amatitlan, extending roughly 65 kilometers between the two points.

As these new highways enter the infrastructure, one must note that completion of them are expedited mostly because of the lack of stronglocalized zoning laws that are efficient and benefit the local population.

As a result, the physical location of these highways are designed and built often with minimal input from those directly impacted. A sort of caveat emptor precludes new projects in the hopes that road building is sustainable, especially in the era of climate change and inclement weather patterns. Even though Guatemala is rich with several different microclimates, global warming does impact the country and is very evident when roads wash out because they were not securely constructed.

This doesn’t reflect poorly on the highway planners; it simply is what Guatemala and other regions around the world can relate, stronger, worsening climate patterns are becoming pronounced. Added to the geography of Guatemala is the topography and this creates undue tension in the region and periodically results in devastation. Fortunately, repairs are expeditious and turn-around is minimal to maintain the flow of commerce.

Aside from road construction projects, in 2021, the Guatemalan president initiated discussions that focused on creating a cargo corridor that is secondary to the main international airport, La Aurora. La Aurora airport is situated inside the capital city and is about a 3 kilometer walk to the hotel zone.

In 2021, Guatemalan President Dr. Giammattei proposed that an older, parachute military airport on the outskirts of Escuintla (60 kilometers south of the capital) be converted into a second regional airport constructed to primarily handle overflow cargo at the La Aurora airport in the city. By separating the two port facilities, one for passengers into the city and the second, for cargo roughly an hour away, this has a twofold benefit. The primary benefit is traffic alleviation and one that routes cargo away from the city to other regional cities. The second benefit is it keeps the base of tourism intact with consistent use of La Aurora airport as the main feeder with regards to commercial tourism.

This port/cargo airport is one that would assist imports coming in and radiating out to the north, as well as exports at the nearby economic zone just outside the Port Quetzal container ship port facilities. Strategic location plays a major

As primary and secondary infrastructure development continues, it is only a matter of time before advanced development, housing, training centers and sustainable living practices become more pronounced leading to a continued upward growth of how workplace efficacy is measured. As infrastructure improves, added workers with an eye towards safety would need to be strengthened. Ditto for labor practices, as they would need to be solidified to reward and compensate the worker for reaching workplace benchmarks.

There are two challenges within what is viewed as competitiveness/efficacybenchmarks. They are at best quantitative and not qualitative; they can be ripe for abuse inside any country that traditionally utilizes low wages in tandem with international corporations.

Expanding and leveraging growing wages and labor rights are emerging. As labor standards improve along with efficient workers, wages can improve incrementally to reduce financial and wealth inequality, including debt burdens. The other challenge lies with what was mentioned earlier, the 15 to 27-year-old demographic (a group that is roughly 5 million out of a total population of 18 million), those who are not employed, employable, or privileged to receive a standard education, something that, as mentioned earlier, is not a birthright. Here, one begins to see a fissure become pronounced on why migratory patterns northward and yes, elsewhere around the world is so prevalent.

Each of the issues mentioned are not insurmountable, but it does require time to develop an awareness and implement a plan that yields positive generational results, something that many non-government organizations (NGO’s) have a proven track record, albeit on a smaller scale.

As the wheels of efficacy continue to churn towards higher competitiveness, evidence of a stronger, readily trainable entry level workforce is picking up traction. Noticeable results will become commonplace in ensuing years.

With each passing day, more countries leap ahead to invest in Guatemala, countries such as South Korea, Israel, Spain, Russia and China have established a mutually conducive, business-based approach, even using vaccine diplomacy and following up with employment opportunities. These countries continue to show a recognition that they can benefit from the Guatemalan workers and are investing in jobs long-term growth. After all, many Guatemalans would relish an opportunity to improve their lives and as the American Vice-President Harris stated, “…..remain in the birthplace of their own home country and family….”

The proof, as they say, will be in the pudding. Incremental progress will need to be transparent, measurable and of initial benefit to Guatemalans, more so than that of their largest trading partner, the United States.